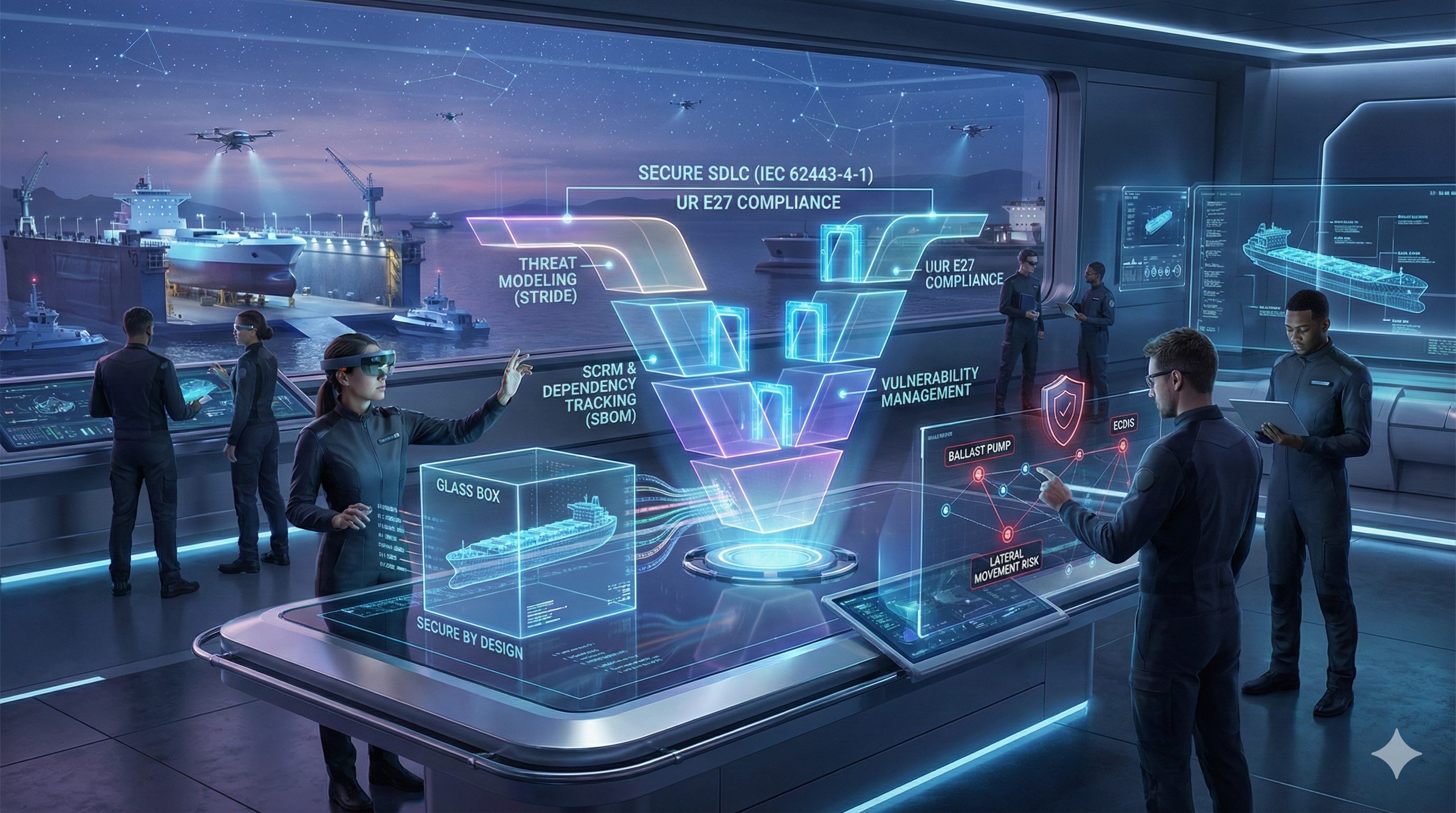

From Black Box to Glass Box: Hardening the Maritime SDLC for UR E27 Compliance

1. The Era of the “Black Box” is Over

For decades, the maritime supply chain operated on a “Black Box” philosophy regarding equipment certification. As a manufacturer, you built a navigation sensor, a ballast pump controller, or an engine management system. You subjected it to environmental testing—vibration, temperature, humidity, and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). You handed the physical unit to a Class surveyor, demonstrated that it functioned under stress, and received your Type Approval. How the software inside was written, or how the libraries were selected, was largely your own business, provided the output was correct.

With the implementation of IACS Unified Requirement (UR) E27 Rev.1 (Sep 2023) for newbuilds contracted for construction on/after 1 July 2024, that era has ended in practice.

The maritime industry has recognized that a device functioning correctly now is not the same as a device that is secure against tomorrow’s threats. UR E27 introduces a structured expectation: suppliers must be able to demonstrate cyber resilience capabilities and lifecycle controls, with required documents available and provided for approval or upon request, depending on scope and Society processes.

A key compliance lever is UR E27 Rev.1 §3.1.6 (Secure development lifecycle documents — typically submitted upon request) and the lifecycle requirements set in UR E27 §5 (Secure development lifecycle requirements).

This is a fundamental shift from pure product validation (testing the object) to process and evidence validation (auditing how security is engineered, verified, delivered, and maintained). The Class Society is no longer just asking, “Does this pump work?” We are asking, “Can you show security was treated as an engineering input across the lifecycle, and can you support it with records?”

This article is a consultative guide to updating internal “Design and Development” procedures. We will show how to transition from “security as a late test activity” to a lifecycle approach that is audit-ready, and how to leverage the structure of IEC 62443-4-1 as a proven framework—while being clear that UR E27 references and expects evidence for selected lifecycle outcomes, not necessarily a full IEC 62443-4-1 certification program.

We will deep-dive into three common stumbling blocks for manufacturers: Threat Modeling, Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM), and Defect/Vulnerability Management.

2. The Foundation: Hardening Your Lifecycle (Not Just the V-Model)

Many Quality Management Systems (QMS) use a V-Model; others use waterfall, agile, or hybrids. UR E27 does not mandate a specific development model. What it does require is that you can show security is handled and evidenced across the lifecycle:

requirements and design inputs

implementation controls

verification of security capabilities (test procedures and records)

secure delivery and updates

hardening and operating guidance

ongoing handling of security issues and dependencies

To comply with UR E27, you must stop treating security as something you “test in” at the end. You must introduce defined security activities and deliverables as part of your normal engineering exit criteria.

The New Architecture of Your Procedure

In your updated procedure documentation, each phase must have a corresponding security output (deliverable) and exit criteria (what “good enough to proceed” means).

Concept / Feasibility → Exit Criteria: High-level cyber risk and environment assumptions

What networks will this device touch? What trust boundaries exist? Who maintains it onboard?

Requirements → Exit Criteria: Cybersecurity Requirements Specification (CRS)

Functional requirements (e.g., “measure pressure”) paired with security requirements (e.g., “authenticated configuration changes,” “default-secure settings,” “logging,” “update authenticity verification”).

Architecture / Design → Exit Criteria: Security design decisions + threat model (recommended)

Trust boundaries, secure boot/update approach, account model, service interfaces, hardening defaults, and compensating controls where protocols can’t be secured.

Implementation → Exit Criteria: Secure coding controls + build integrity controls

Coding standards, code review rules, static analysis, secrets handling, dependency pinning, reproducible builds where feasible.

Verification & Validation → Exit Criteria: Security capability verification evidence

A repeatable test procedure and results. This can include negative testing, vulnerability scanning, targeted fuzzing, and penetration testing where appropriate—but the key is documented, repeatable verification aligned to your claimed capabilities.

Release / Delivery → Exit Criteria: Secure update and delivery readiness

Evidence of update authenticity controls (signing, verification) and protection of the signing keys; release notes; SBOM; customer-facing security configuration/hardening guidance.

Maintenance → Exit Criteria: Vulnerability intake + dependency monitoring + patch communication

A defined process for monitoring, triage, impact analysis, and update delivery.

This sounds rigid, but it’s exactly what makes your SDLC “defensible” during plan approval and supplier audits.

Practical note: UR E27 does not require a certified lab or “qualified external tester” to carry out security capability testing. What it does require is that your testing is credible, repeatable, and evidenced.

3. Deep Dive: Threat Modeling as a Design Output (Practical, Not Theoretical)

(Aligned with IEC 62443-4-1 “Secure by Design” practice concepts)

The most frequent gap we identify during supplier audits is not “lack of security features.” It is lack of engineering justification: why those features exist, what threats they address, and what assumptions are made about the operating environment.

The “So What?” Factor: Addressing Engineering Skepticism

When we ask for threat modeling for a seemingly benign device—say, a ballast pump controller or a level sensor—the common pushback is:

“Who would hack a ballast pump? There is no financial data there.”

That is not how modern OT compromise works. Attackers rarely target a ballast pump because they “want the pump.” They target it because it is a networked computer, sometimes with weak maintenance interfaces, outdated components, or default credentials.

The Risk is Lateral Movement and System Impact.

A compromised controller can become a foothold (pivot point) on the vessel’s OT network. From there, an attacker can scan for higher-impact systems (automation servers, HMIs, network infrastructure, engineering workstations), disrupt operations, or manipulate process data. Your device’s job is not only to function—it must not become the weakest link.

Execution: Use a Method, Don’t Wing It

UR E27 does not prescribe STRIDE (or any single method). However, your procedure should mandate a consistent methodology. STRIDE is a practical choice for embedded vendors because it is structured and teachable.

Let us walk through a STRIDE-style analysis for a typical maritime component: a Smart Pressure Sensor connected via Modbus TCP.

S — Spoofing (Identity / Endpoint Impersonation)

Threat: An attacker impersonates a controller and sends configuration changes; or spoofs sensor readings upstream.

Design Fix: Where feasible, implement strong authentication for configuration changes (service tools, maintenance sessions). If Modbus TCP cannot be authenticated at protocol level, enforce authentication at the management interface (service port, web UI, engineering tool) and document required network controls.

T — Tampering (Data Modification)

Threat: Sensor values or setpoints are modified in transit, causing unsafe control actions.

Reality check: Modbus TCP has no built-in integrity/authentication. “Just add HMAC” is often not interoperable.

Design Fix: Provide integrity/authentication via standardized secure transport (e.g., TLS/VPN/gateway) or specify compensating controls (segmentation, ACLs, whitelisting, conduits) as part of the expected environment. Your design documentation must clearly state which path you support and what the ship/system integrator must provide.

R — Repudiation (Denial of Action)

Threat: A technician changes calibration or thresholds and later denies it.

Design Fix: Secure logging of configuration changes with timestamp, user identity (or service tool identity), and event integrity protections appropriate to the platform.

I — Information Disclosure (Data / Secrets Leakage)

Threat: Debug services, default credentials, memory dumps, or sensitive configuration exposed (Telnet, debug UART, verbose logs).

Design Fix: Disable debug services in production; harden defaults; encrypt or protect secrets; remove developer backdoors; document service access procedures.

D — Denial of Service (DoS)

Threat: Flooding network connections starves CPU and stops reporting.

Design Fix: Rate limiting, connection caps, watchdogs, and prioritization so the sensor loop remains stable under network stress. Document limits and expected network hygiene.

E — Elevation of Privilege

Threat: A low-privilege function is exploited to gain admin/root level execution.

Design Fix: Least privilege for network-facing processes, safe memory handling, secure coding rules, and hardening of maintenance tools.

Implementation in Procedures:

Your “Design Phase” procedure should require a Security Design Record (or Threat Modeling Report) that:

lists threats in a consistent structure

links each to a mitigation (design decision, control, or compensating requirement)

records assumptions about the operating environment (segmentation, access controls, service workflow)

produces traceable security requirements for implementation and test

This is what makes your security posture auditable instead of “hand-wavy.”

Practical tip: when security depends on environment controls (segmentation, jump hosts, firewall rules), state this explicitly. UR E27 expects clarity on defence-in-depth measures expected in the environment, not only product internals.

4. Deep Dive: Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) & Dependency Tracking (SBOM Done Right)

(Aligned with IEC 62443-4-1 “Management of Security-Related Issues” concepts; strongly supports UR E27 lifecycle expectations)

When we discuss “inventory,” manufacturers often think “shipowner asset inventory.” That is not the point here. The audit focus is on your internal inventory of software components—especially third-party and open-source dependencies.

The “Left-Pad” Problem in Maritime Firmware

Modern firmware is rarely written from scratch. Common components include:

TCP/IP stacks (e.g., lwIP)

crypto libraries (OpenSSL, mbedTLS)

embedded web servers (admin UI)

parsers/serializers (XML/JSON/protocol parsing)

If a vulnerability is found in a dependency version you ship, your product may inherit that vulnerability.

The Logic of an SBOM (and What Auditors Actually Need)

To be audit-ready, your procedure should mandate the creation of a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) per firmware build/release.

Think of an SBOM like an ingredients list:

Component name

Version

License

Source / origin

Build inclusion (statically linked? optional module? only in dev builds?)

But an SBOM alone is not enough. Auditors (and customers) will immediately ask:

Which product lines and firmware versions include the vulnerable component?

Which customers/shipsets received those versions (fleet mapping)?

What is your decision and action plan?

So your procedure must also maintain release traceability (product → firmware version → shipped units/customers).

The Audit Trap: Spreadsheets vs. Repeatable Traceability

The failure pattern looks like this:

Auditor: “A critical vulnerability was announced in a library last week. Do you use it?”

Manufacturer: “Let me check…” (spreadsheets, phone calls, hours of uncertainty)

That response is a process failure, not a tooling failure.

You do not necessarily need a full CMDB. You do need:

SBOM generation integrated into build/release

a single source of truth for “what ships with what”

the ability to perform impact analysis quickly and consistently

This can be achieved with an SCA tool, SBOM tooling (SPDX/CycloneDX), and disciplined release management.

Process Requirement: Continuous Vulnerability Monitoring + Impact Analysis

Documentation is dead if it is not updated. Your procedure must define a process for continuous monitoring:

Monitoring trigger: automated alerts or scheduled review cadence (define it)

Triage & severity: internal severity method (CVSS is common; document how you use it)

Impact analysis record: affected/not affected with technical justification

Decision & actions: patch, mitigation guidance, compensating controls, or “no action” (with evidence)

Example (audit-friendly wording):

Finding: Vulnerability in crypto library version X

Assessment: We use the library, but the vulnerable feature is not enabled/compiled; evidence attached (build flags/config)

Decision: No product update required; advisory issued to customers if needed

The key is the paper trail. Without it, you cannot prove you manage dependency risk.

5. Deep Dive: Defect Management & Vulnerability Disclosure (PSIRT Reality)

(Aligned with IEC 62443-4-1 “Security Update Management” concepts; supports UR E27 lifecycle expectations)

The final pillar is what happens after the product leaves the factory. A mature approach must cover receiving, analyzing, and resolving security defects, and delivering updates securely.

The “Bug” vs. “Vulnerability” Distinction

Most manufacturers have a bug tracker (Jira, Bugzilla). A common mistake is to treat security vulnerabilities exactly like functional bugs.

Security defects require different handling for three reasons:

Confidentiality: Security flaws may need restricted handling until a fix is ready.

Urgency: Critical security issues may require out-of-cycle fixes.

Coordination: You may need to coordinate with customers, integrators, or third parties before public disclosure.

Your procedure must define a separate workflow (or “security flag”) with restricted access, defined triage steps, and controlled communications.

The Public Interface: If You Don’t Offer One, You Won’t Get Reports (Or You’ll Get Them Too Late)

A security researcher or customer needs a clear channel to report issues.

Minimum expectations for an audit-ready posture:

Email alias:

security@yourdomain.comorpsirt@yourdomain.comPublished process: a

/securityor/vulnerability-disclosurepage describing how to report and what to expectOptional but recommended: PGP key or secure reporting mechanism

Service Levels (SLAs) — You Must Define Timelines, Even If They’re “Internal Targets”

Your “Defect/Vulnerability Management” procedure must define response targets. The numbers below are examples, but you must have your own defined values:

Acknowledgement: within 72 hours

Initial assessment: within 5 business days

Remediation target:

Critical: patch/advisory within 30 days (or documented mitigation plan)

High: within 60 days

Medium/Low: next scheduled maintenance release

What Class and customers will look for is not “perfect speed.” It is predictability, control, and evidence of execution.

6. Conclusion: The Business Case for Compliance (and Why This Isn’t Just Paperwork)

Updating your “Design and Development” procedures to meet UR E27 expectations is not a small change. It requires stronger documentation discipline, clearer design records, better release traceability, and lifecycle security controls.

However, beyond UR E27 compliance, the business value is real:

Reduced liability and clearer responsibility boundaries: Evidence of design decisions, hardening defaults, and update controls demonstrates due diligence.

Market differentiation: SBOM readiness, credible vulnerability handling, and secure update mechanisms increasingly influence vendor selection.

Lower field cost: Better verification and dependency control reduce painful incidents and emergency service events.

Next Steps for Your Team:

Gap analysis: Map your current SOP to lifecycle security outcomes (and optionally the 8 IEC 62443-4-1 practice areas as a structured checklist).

Tooling: Implement SBOM generation + release traceability + vulnerability monitoring (SCA/SBOM tooling).

Training: Run a practical threat modeling workshop (STRIDE or equivalent) focused on your actual product interfaces and service workflows.

Procedure rewrite: Add security deliverables and exit criteria to each phase; explicitly cover update authenticity and key protection, hardening defaults, and environment defence-in-depth expectations.

The Class Society will assess evidence against the rule intent and approval scope. The more your procedure reads like engineering reality—with traceable records—the smoother your approval cycle will be.

Appendix A: Checklist for Updated Procedure Headers (Audit-Ready)

Ensure your updated procedure document contains sections covering the following (use as internal headings):

Security Management (SM): roles/responsibilities; security ownership; approvals

Specification of Security Requirements (SR): how CRS is derived and traced

Secure Design (SD): interface inventory; trust boundaries; threat modeling method (recommended); design decisions; compensating controls and environmental assumptions

Secure Implementation (SI): coding standards; reviews; static analysis; secrets handling

Security Verification & Validation (SV): repeatable security capability verification; negative testing; vulnerability scanning; evidence retention

Management of Security-Related Issues (DM): SBOM; dependency pinning; monitoring triggers; impact analysis workflow

Security Update Management (SUM): secure update delivery; authenticity verification; protection of signing keys; customer communications

Security Guidelines (SG): security configuration guidelines including default values and recommended hardening settings; operational constraints and expected environment controls